AVEBURY'S

MOST-INTERESTING NEARBY SITES:

SILBURY HILL

(SU 100686). Silbury, the biggest prehistoric artificial

mound in Europe, can be adequately regarded and photographed from nearby viewing

areas, but access to the hill is not permitted. Silbury

is a grass-covered chalk mound in the shape of a flat-topped cone

The latest evidence from radio-carbon dating suggests that Silbury was built

about 4300 years ago, at the end of Avebury's lengthy stone-building period

(Alasdair Whittle, Sacred Mound and Holy Rings). The height

of Silbury is 40 metres (130 feet), diameter 160 metres (522 feet) at the

base, and the monument covered 2.2 hectares (5.5 acres). Almost half-a-million

tons of chalk were shifted to achieve this.

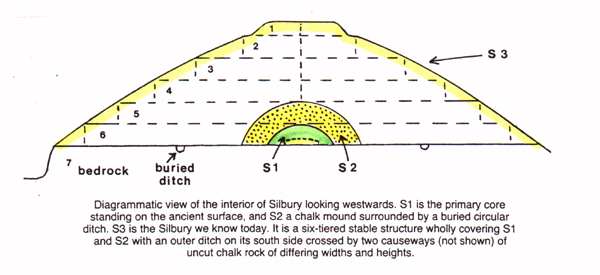

In his report on the Silbury excavations undertaken by Richard

atkinson in 1968-1970, Dr Whittle calls Silbury Hill a 'sacred mound'

because he sees it as having been built as a consequence of the Neolithic

people's belief in a Mother Earth religion.

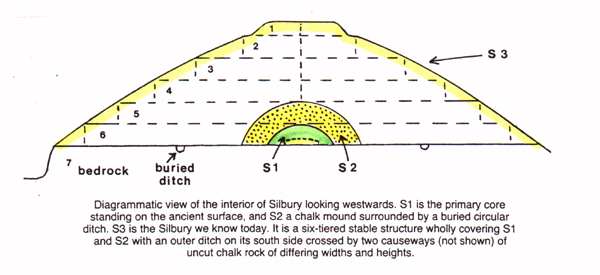

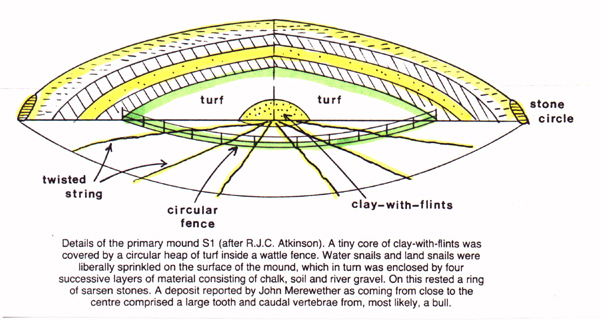

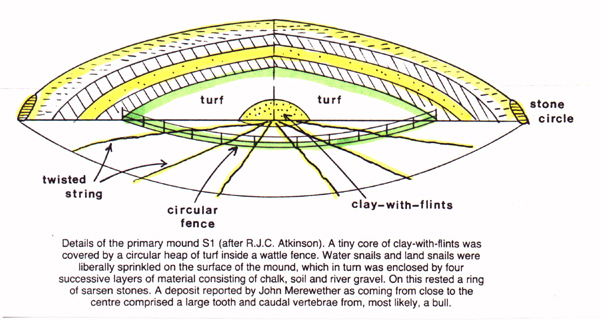

Only in the innermost core have excavators found materials other

than chalk. Chief among these was a circular stack of turf (height

3.5 metres) centred by a small mound of clay surrounded by a wattle fence

20 metres in diameter. Covering the turf and the fence were 4 successive

layers of chalk gravel and topsoil, each layer half-a-metre deep, leading

to a primary mound 5.5 metres high with a circumference of 36.5 metres.

Reclining on its sloping sides were sarsen stones scattered with fragments

of bone and twigs and forming a stone circle. The 19th-century excavator

who discovered these items (Dean Merewether) also found at the centre of

the mound, on the ancient grass surface, the 'caudal vertebrae of the ox,

or perhaps the red deer, and a very large tooth of the same animal'.

Such deposits have the appearance of a ritual character.

D.W.A. Startin has estimated the labour of building

Silbury as 4 million man-hours. The final apparent volume was 350 000 cubic

feet, of which 250 000 cubic metres were moved by hand, the volume difference

arising from the inclusion of a cut-off spur of natural chalk. It probably

took 40-50 years of labour to build Silbury.

What may be another but smaller Neolithic mound is at

Marlborough in the grounds of the Public School five miles (8 km) to the

east. Its volume is about 50 000 cubic metres and its present height 20 metres.

Quantities of antler picks have been taken from this much-abused conical

hill whose steep sides indicate that it possesses a planned stability comparable

with Silbury.

WEST KENNET LONG

BARROW (SU 105

677) This splendid chambered megalithic monument is open at no

charge at all reasonable times of day. The property belongs

to the British nation and is cared for by the National Trust. It is

close to Silbury Hill and can be reached from the main road (the A4) by walking

along a narrow uphill track, which takes about 10 minutes. Two lay-bys

provide parking for cars.

The monument is a fine, restored Early Neolithic chambered barrow.

Inside, 5 chambers lead off from a central gallery. All chambers and

roof are built from huge sarsen stones. Carbon-dating estimates

suggest a foundation date of circa 3700-3600 BCE and a closure date about

1200 years later. At the time of sealing the barrow, a facade of huge

sarsens was placed immediately in front of the entrance in the manner of

blocking stones. The central megalith has a vertical groove over 2

metres long incised upon it. This appears to be a female sign or yoni/vulva

mark and stands before the main gallery which is aligned east-west.

The remains of skeletons and simple grave goods

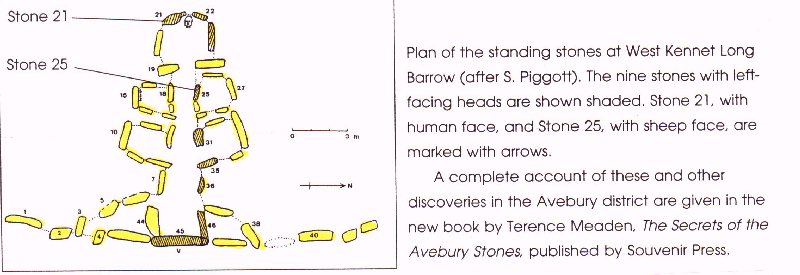

were found by the excavators in 1859 and 1955. The small skull of an

infant was positioned on the floor between Stones 21 and 22, in such a way

that it would have been lit by the light of the rising sun at the equinoxes.

At the back of the south-west chamber, in front of Stone 16,

lay three skulls ---- those of a child, a young adult, and an aged person.

A megalith of this south-west chamber (Stone 13) has three, probably-natural,

shallow cups on it.

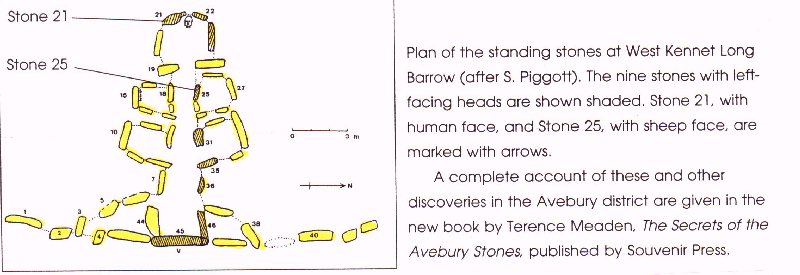

The most remarkable discoveries of recent

years at this site are the carved megaliths inside the barrow (see

plan).

Two of the carved megaliths are outstanding : Stones 21 and

25.

One is a realistically-shaped human head

in left-facing profile (Stone 21, shown below, right, as

a sketch). Its several features are in perfect human proportion, and

demonstrate a high level of artistic competence for such a difficult medium

that was hitherto quite unknown for early Britain. Stone 22,

next to it, has the general appearance of a skull with domed cranium.

In the main gallery facing this human head is another major

carved stone (Stone 25, see photograph, left, below). This takes

the form of a left-facing sheep's head.

Because of the barrow's alignment with the rising sun at the March equinox,

the arrangement has been interpreted as indicating an annual ritual involving

a mid-spring lambing festival (when the sun illuminates the sheep-stone) within

a rebirth tomb of the dead. Scholars conversant with archaeology and

ancient religions interpret the megalithic chambered barrow as

having a prepared interior which stands for the vagina and womb of the Earth

Mother, a spiritual concept which is supported by the yoni-carving on the

entrance stone on the same alignment. In fact, when the long barrow

was in use, the sun penetrated the length of the gallery to the end-cell

where it fell upon Stone 22 (which is skull-shaped), next upon the genuine

child's skull, and lastly upon the finely-carved left-profile human head.

Many details of these and other carvings at this barrow

are set out in the latest book about Avebury discoveries indicated in the

figure caption above. CLICK.

.........

.........

.........

.........